By Zimba Wave International desk

The fatal stabbing of three young girls at a dance class in the seaside town of Southport, in the north of England, has been followed by the worst unrest the UK has seen in more than a decade.

The violence, in towns and cities across England and in Northern Ireland, has been fuelled by misinformation online, the far-right and anti-immigration sentiment.

Why did the killing of children in Southport lead to violence?

On 29 July, Bebe King, six, Elsie Dot Stancombe, seven, and Alice da Silva Aguiar, nine, were killed in a knife attack at a Taylor Swift-themed dance and yoga event. Eight more children and two adults were injured.

Later that day, police said they had arrested a 17-year-old from a village nearby and that they were not treating the incident as terror-related.

Almost immediately after the attack, social media posts falsely speculated that the suspect was an asylum seeker who arrived in the UK on a boat in 2023, with an incorrect name being widely circulated. There were also unfounded rumours that he was Muslim.

In fact, as the BBC and other media outlets reported, the suspect was born in Wales to Rwandan parents.

Police urged the public not to spread “unconfirmed speculation and false information”.

The following evening, more than a thousand people attended a vigil for the victims in Southport. Later on, violence broke out near a local mosque. People threw bricks, bottles and other missiles at the mosque and police, a police van was set alight and 27 officers were taken to hospital.

The disorder was widely condemned. Local MP Patrick Hurley said “thugs” had travelled to the town to use the deaths of three children “for their own political purposes”, while Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer denounced the “marauding mobs on the streets of Southport”.

How did the violence spread?

There had been discussion of the rally on regional anti-immigration channels on the Telegram messaging app. Police said the violence was believed to have involved supporters of the now disbanded far-right group the English Defence League (EDL).

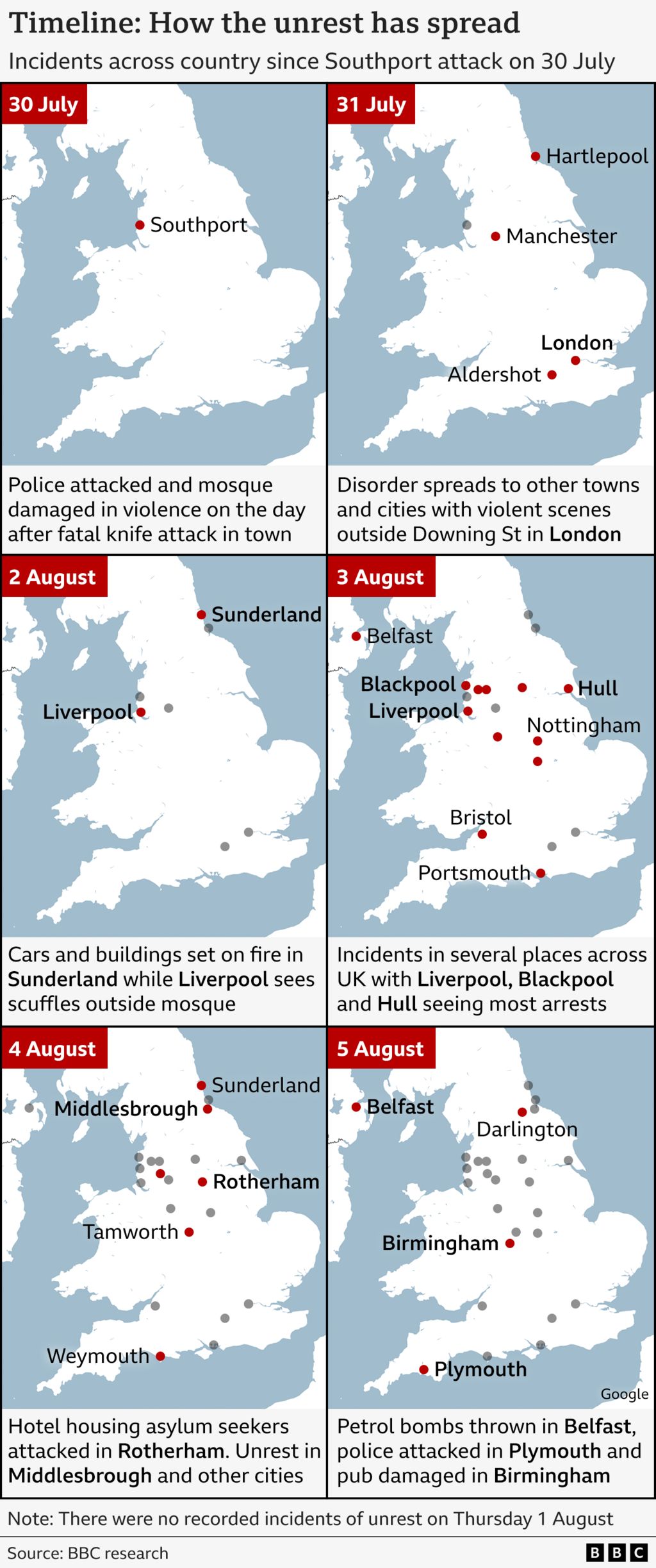

The day after the Southport riot, violent protests in London, Hartlepool and Manchester broke out, which police linked to Southport. More took place throughout the week – with many targeting mosques and hotels housing asylum seekers.

While there was no single organising force at work, BBC analysis of activity on mainstream social media and in smaller public groups shows a clear pattern of influencers driving a message for people to gather for protests.

Multiple influencers within different circles amplified false claims about the identity of the attacker, reaching a large audience – including ordinary people without any connection to far-right individuals and groups.

On X, EDL founder, far-right activist and convicted criminal Tommy Robinson, whose real name is Stephen Yaxley-Lennon, posted inflammatory messages to his nearly a million followers while on holiday in Cyprus.

An influencer on X associated with Yaxley-Lennon, who posts under “Lord Simon”, was among the first to publicly call for nationwide protests.

Where have riots taken place and what has happened?

Riots have since broken out across England, from Plymouth on the south coast to Sunderland in the North East. There have also been riots in Belfast, Northern Ireland.

Crowds attacked mosques and accommodation housing asylum seekers, cars and buildings, including a library, were set on fire, and shops looted.

Violence in south Belfast, where anti-immigration and anti-racism protesters faced off in tense scenes outside the city hall, involved “racist elements”, a judge has said. Police are investigating an assault on a man whose head was reportedly stamped on as a racially motivated hate crime.

In Rotherham on Sunday, terrified staff at the Holiday Inn, which was housing asylum seekers, described how they stacked fridges and other furniture against a door to barricade themselves against a mob which had smashed its way into the building. Nearby residents described fleeing their homes as rioters entered their gardens.

Dozens of police officers have been injured, some receiving hospital treatment.

Merseyside Police’s chief constable said some of the officers injured “feared they would not make it home” to their families.

The spate of violence has prompted concern from outside of the UK. Malaysia, Nigeria, Australia and India have all issued travel advisories, urging people to stay vigilant and avoid protests.

Who has been involved in the UK riots?

It is a “nuanced picture” with a degree of local coordination, but also many instances of “locals reacting to what they’re seeing on social media, what they’re seeing outside in their streets and just joining in”, a police source told PA news agency.

BBC Home Affairs Editor Mark Easton was in Sunderland on Friday night, where he said far-right rioters attacked police, set fire to an advice centre next door to a police station, threw stones at a mosque and looted shops.

But as well as masked thugs, he also saw families cheering them on – mums and dads with pushchairs and children draped in the St George’s flag.

While some have been intent on violence, there were initially also people with concerns about immigration wanting to exert their right to peaceful protest.

One such person, who joined an anti-immigration protest in Rotherham on Sunday, told the BBC violent scenes at a hotel housing asylum seekers were “absolutely barbaric… this is not what we’re here for”.

Others may be lashing out in a general sense of frustration, according to a volunteer at Abdullah Quilliam Mosque in Liverpool.

In several cities, violent groups have clashed with counter-protesters. In Bristol, anti-racism protesters said they locked arms to stop rival demonstrators from storming a building housing asylum seekers.

There was unrest in Birmingham when a group – comprising of mainly young Asian men – gathered to oppose a rumoured far-right march that did not materialise.

How have police and the UK government responded?

More than 400 arrests had been made by Tuesday 6 August, police say. They include children as young as 11.

Sir Keir has condemned what he called “far-right thuggery”. He has promised charges and convictions, “whatever the apparent cause or motivation”, and said those participating in violence, including those “whipping up this action online”, would regret it.

The government said a “standing army” of specialist officers will tackle the disorder, and police forces would share intelligence on violent groups

It said it was also working with social media companies to ensure misinformation and disinformation is removed.

And it has said it will make more than 500 new prison places available to ensure those taking part in the violence could be jailed.

Prosecutors are considering terrorism offences for some suspects, alongside the extradition of influencers allegedly playing a role in the disorder from abroad, the director of public prosecutions told the BBC.

What are communities affected by the riots doing?

Volunteers rebuild the fence outside Southport Islamic Society Mosque

In many areas locals have rallied in the face of violence, with clean-up operations and shows of solidarity with those affected in full force.

In Southport, dozens of local residents – still in shock from Monday’s killing of the girls – turned up with brushes and shovels to help after the violence.

Tradesmen also offered to rebuild walls and replace windows for free.

Fundraisers have been launched for some of those affected – one, set up to show appreciation for a mosque in Hartlepool, saw its initial target of £200 surpassed in 15 minutes.

Faith leaders in Merseyside have called for people to “remain calm and peaceful” in the wake of the Southport knife attack, and remember there is “far more that unites than divides us”.